Why Has the Number of Public Companies Declined?

The recent near-highs of the stock market are masking a trend from the last few decades: The number of publicly traded U.S. companies has dropped significantly. In 1996 the number of listed companies in the U.S. peaked at 8,090, but as of Q1 2023, it had fallen to 4,572, a drop of 43%.[1] The chart below highlights this dramatic decrease in public companies, which occurred in spite of growth in the economy, global market expansion, and new industries and technologies.

Source: World Bank and Statista

To help put this decline in perspective, we can also look at the number of listed companies per million people. In 1996, there were 30 public companies per million people in the U.S., but that number fell to only 14 in Q1 of this year, a 53% drop. Yet at the same time, access and cost for investors to trade stocks improved. This article explores possible reasons for this phenomenon and implications for investors.

Backdrop

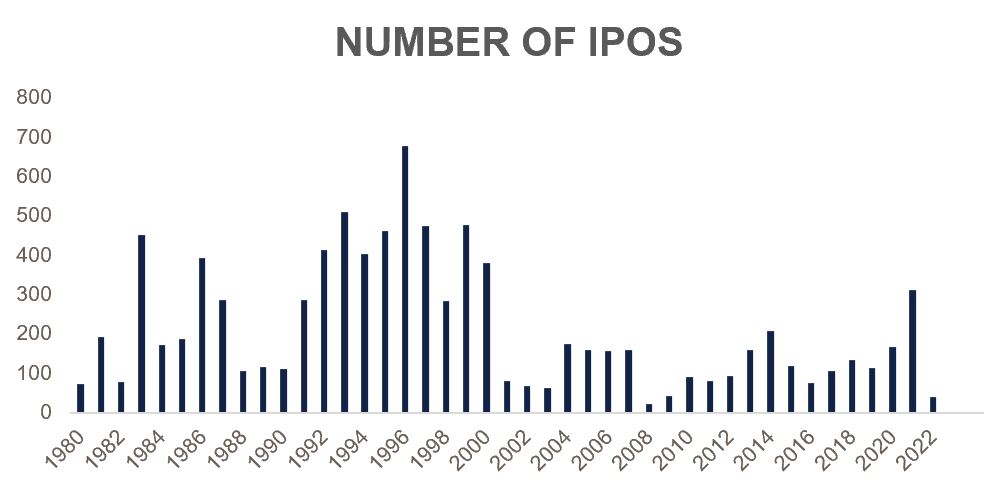

Thirty years ago, commissions for stock trading were very high, the 10-year Treasury yield was at 6%, and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) were mostly a footnote in the investment landscape. In 1975, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had relaxed commission rates for equity trades, which ushered in an era of discount commission brokers such as Charles Schwab and Ameritrade. Less expensive trading for investors, especially in retail, coincided with the start of the 1980 bull market. The combination of low-cost trading and a strong stock market helped fuel an initial public offering (IPO) surge. Unfortunately, this timeframe turned out to be the peak in the number of public companies in the U.S.

Source: Jay Ritter, University of Florida

Individual Stock Selection vs. Broad Market

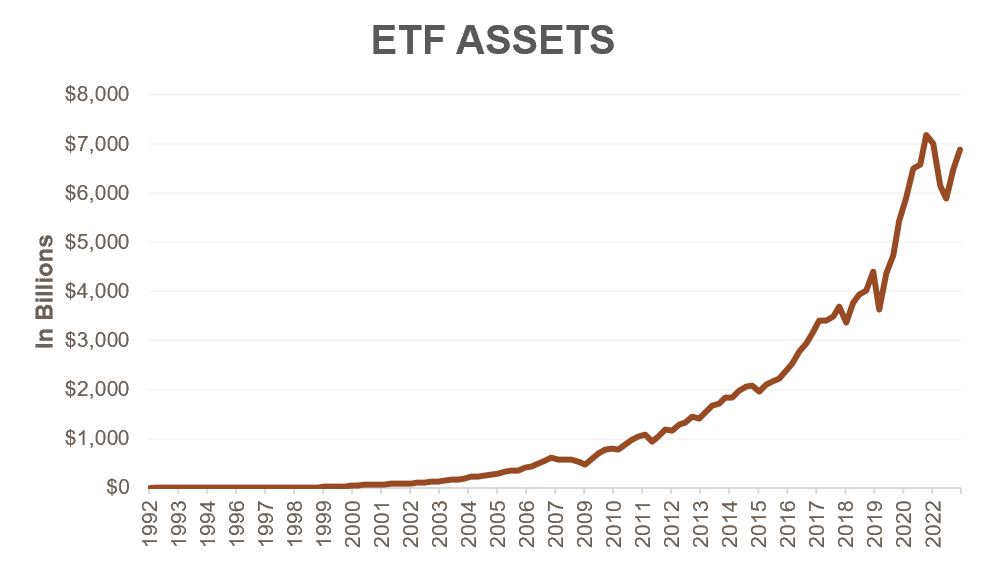

The strong stock market also attracted significant attention from academia, and resources were deployed by the investment community to understand stock market returns and risk. Some experts believed that the markets were becoming more efficient because of the proliferation of information. Others maintained that pockets of inefficiency still existed and could be exploited for gains. The former group gradually expanded, and investor advocates such as John Bogle of Vanguard became proponents for a new investment approach—rather than trying to beat the market, investors could mimic the market and do it at a low cost. They could buy ETFs designed to replicate the return of a broad market benchmark.

Buying the market allows investors to participate in broad market moves without the need to research and select individual stocks. Although active managers have continued to thrive, the trend toward indexation has been in place now for decades. The rise of this type of investing coincided with the decline in the number of public companies and IPOs.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

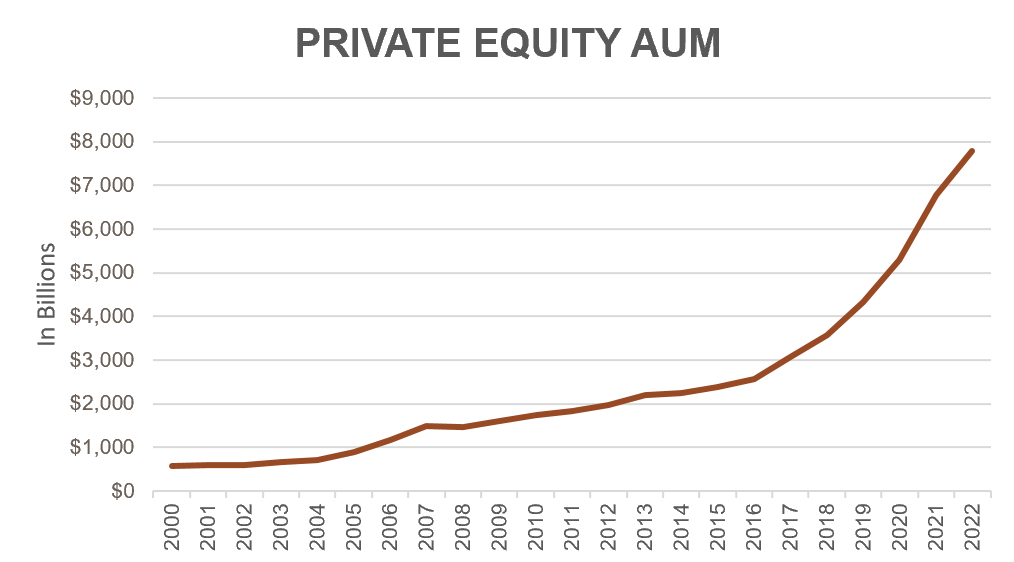

Rise of Private Equity

What we also saw in the 1980s was the emergence of private equity[2] firms and their high-profile dealmaking, some of them famous while others were infamous. At that time, the “barbarians at the gate” were investors who could pool funds of other investors with their own, invest in public companies, and then improve operations to make them more profitable and valuable. Often, for better or worse, financial engineering was part of the equation too. These private equity firms promised better returns for their wealthy investors using a vehicle, private equity funds, that enjoyed less regulatory scrutiny. Although the term private equity is used, other variations of private vehicles exist depending on the type of investment. Some focus on early stage or venture capital investing while others have expertise in buyouts or growth equity investing.

Source: Preqin

The private equity industry has grown and matured. Some investors in these funds were even tied to academia, such as David Swensen of Yale who was an early advocate of using private vehicles in Yale’s endowment fund. That fund, with its perpetual life, could afford to be patient with these private vehicles and did not need the daily liquidity of public securities. Mr. Swensen’s top-tier performance attracted the attention of other endowments and large institutional investors. He and others replicating the endowment model ushered in a period of significant growth for private equity firms.

Regulatory Burden

Public companies enjoy broad retail and institutional ownership that allows them to raise capital from a wide audience. These companies can benefit from the capital raised in an IPO and ongoing access to the capital markets as well as the use of their stock for acquisitions. In return for this access to public markets, the companies must adhere to significant regulatory requirements. The Securities Act of 1933 was signed into law during the Great Depression following the stock market crash of 1929. That law and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 form the basis for much of the regulatory framework in the public markets. Following the dot-com bubble that ended in 2000, along with several high-profile scandals, including WorldCom and Enron, the Sarbanes-Oxley law was passed to protect investors. It’s an extensive law that addresses many aspects of public companies including accounting, auditor independence, and executive responsibility for financial reports. It even has provisions for securities analysts to maintain independence and avoid conflicts of interest.

With regulations now even more strict and liability for executives greater, companies have been incentivized to avoid the public markets. The rise of private equity was a timely tool for management to tap the capital markets without the burden of excessive regulation. Quarterly financial disclosures for public companies also tend to focus investor attention on short-term results and away from long-term strategic thinking. Like clockwork, the quarterly earnings season narrows in on whether companies meet, beat, or miss earnings and sales results versus analyst expectations for the quarter. Private companies can avoid this constant cycle. This does cut both ways, however; transparency is generally good but too much can, and does, encourage short-term decision-making.

Globalization and Consolidation

Many industries have undergone consolidation to become more competitive in the highly globalized economy. Smaller companies may find it difficult to compete with multinational firms with the scale to drive down costs. Again, with the addition of the regulatory burden, consolidation results in fewer companies. It’s also likely that the global nature of markets may encourage companies to shop around for the best regulatory environment, though the U.S. has the most developed capital markets in the world.

Investor Implications

Although more than 4,500 public companies in the U.S. would appear to offer plenty of choices for investment, the drop in the number of companies may indicate a smaller and changing opportunity set. The highly transparent public securities, with their regulatory framework, may not be the ideal source of capital for many companies. Firms that wish to avoid the scrutiny and quarterly earnings treadmill have the ability to succeed in the private markets. Investors that solely invest in public securities are missing the opportunity to take advantage of private companies. Not only is the opportunity set smaller in relation to the total, but these public companies may have a lower growth profile as many technology companies can stay private for a longer period of time.

The combination of corporate management’s desire to avoid public scrutiny and the rise of private funds has delayed the day that many companies “go public.” This trend has been particularly evident in recent years with technology companies that have business models that can scale up quickly. In fact, many tech companies may be less capital intensive than firms in other industries. Software is based on intellectual property and less on tangible assets such as buildings, equipment, and land. The ability to delay an IPO has created some large start-ups. These firms, with a value of more than $1 billion, are known as unicorns. By staying private, these unicorns deny public securities investors the opportunity to participate in these growing businesses.

While the number of public companies has decreased, some of the most dominant companies are still public. Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and Google (Alphabet) went through the IPO process and now enjoy significant market shares in their respective industries and trillion-dollar-plus public stock market capitalizations. These companies have also acquired smaller companies, leading to the consolidation discussed earlier and fewer public companies. The rise of private equity investing also is raising the ire of the SEC. It’s been recently reported that the SEC is ready to add rules to increase transparency and competition in the private funds industry.

The U.S. is a remarkable generator of ideas and wealth. The stock markets are an integral part of this success, with IPOs often being the public culmination of this entrepreneurship. Although IPOs and the number of public companies have declined, businesses and their investors have the option of private markets for capital. It has become easier to participate in the private markets as competition has expanded and fund structures and fees have become more investor friendly. So while the number of public companies is lower, the overall equity markets, public and private, remain robust and continue to fuel the growth of U.S. companies and the economy.

[1] Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

[2] Private equity funds are speculative investments and are not suitable for all investors, nor do they represent a complete investment program. Private funds are available only to qualified investors who are comfortable with the substantial risks associated with investing in private funds. An investment in a private fund includes the risks inherent in an investment in securities.

As with any investment strategy, there is potential for profit as well as the possibility of loss. Blue Trust does not guarantee any minimum level of investment performance or the success of any investment strategy. All investments involve risk and investment recommendations will not always be profitable. Diversification does not guarantee investment returns and does not eliminate loss. Past performance does not guarantee future results.