Federal Reserve Independence: Myth or Reality?

“The President Shoves the Federal Reserve Chairman and Yells at Him for Not Lowering Rates”

Did you miss this headline? These events happened…but not recently. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson and Federal Reserve Chairman Bill Martin engaged in a heated exchange over Martin’s decision to raise interest rates to counter inflation fears. Instead, Johnson wanted rates lowered to help finance the Vietnam War and domestic spending. While the conflict between presidential agendas and Federal Reserve (Fed) monetary policy is very publicized today, this tension has existed since the founding of the Fed in 1913. This blog will review what it means to have an independent Fed, why it’s important, and whether it is truly independent.

Federal Reserve Structure

The Fed was founded to help restore confidence in the banking system following a series of banking panics. In its early years, the Fed operated with less independence, as the Federal Reserve Board included the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency―both appointed by the President. The Great Depression brought major changes, as critics blamed the Fed’s ineffective monetary policy for worsening the crisis. Reforms that followed created the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), shifting control of open market operations from the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks to the Board of Governors. These changes also reduced direct political influence by removing the Treasury Secretary and the Comptroller from the Board.

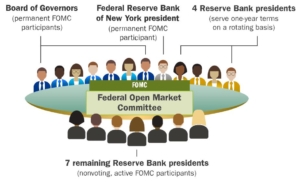

Today, the Fed Board of Governors is comprised of seven governors, appointed by the U.S. President to serve staggered 14-year terms. The lengthy terms are designed to prevent any single administration from dominating the Board. Alongside the Board, 12 Federal Reserve Banks operate separately within distinct regions. Monetary policy is set by the FOMC, a 12-member group composed of the seven Board of Governors appointees, the President of the New York Fed, and four rotating presidents from the remaining Reserve Banks.

Source: www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fedexplained/who-we-are.htm

Why is the Structure Important?

Independence implies being free of influence, but there should also be accountability. The lengthy terms of the governors provide some separation from the presidents who nominated them. Although presidents are political by nature, they are also accountable to voters. In a democracy, monetary policy maintains some culpability to voters, instead of being managed entirely by an insulated group of bureaucrats. In addition, Congress created the Fed and maintains oversight through semiannual reports and testimony to various House and Senate committees. Congress also requires that the Fed promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. These directives are typically called the “dual mandate” because the third goal is often achieved when the first two are met.

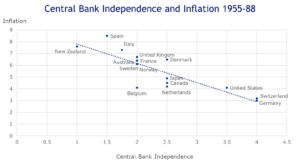

Although the Federal Reserve maintains ties to the President and Congress, it is essential that it operates as independently as possible. This autonomy allows the Fed to raise interest rates to cool an overheated economy or to resist political pressure to lower rates for short-term gain. Studies have confirmed that countries with independent central banks often realize lower inflation. A well-known study from Alesina and Summers in 1993 found this correlation to be true for developed economies (see chart).[i] Most countries, both developed and emerging, recognize this relationship and have moved toward strengthening central bank independence.

Source: Alesina, Alberto & Summers, Lawrence H, 1993. “Central Bank Independence and Macroeconomic Performance: Some Comparative Evidence,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Blackwell Publishing, vol. 25(2), pages 151-162, May.

Historical Examples

Over time, the Federal Reserve has broadened how it interprets and applies its dual mandate of maximizing employment and stabilizing prices. Soaring inflation in the 1970s led Fed Chairman Paul Volcker to dramatically raise interest rates to crush inflation. While these high rates contributed to a recession and higher unemployment, they ultimately succeeded in reducing inflation and curbing expectations of further price increases. Without some level of independence, the Fed may have been reluctant to make those dramatic moves.

During both the Great Recession of 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed cut rates to near zero but also initiated quantitative easing by purchasing long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. These actions injected liquidity into the financial system and helped lower long-term rates. The Fed also expanded its role by extending credit to non-bank financial institutions. Were these actions within the Fed’s mandate, or were they a response to public and political pressure to “do something”? Perhaps a little bit of both.

From a market perspective, central bank independence reassures investors that economic data, rather than political agendas, will dictate monetary policy decisions. If markets suspect a central bank is willing to tolerate higher inflation, bond investors may demand higher yields. Here in the U.S., we have already seen long-term rates edge up while short-term rates declined in anticipation of additional cuts to Fed rates. Although an upward-sloping yield curve is normal, high long-term rates increase mortgage rates, government interest costs, and corporate borrowing rates. For the stock market, rising rates may sway investors to shift to bonds and also reduce the present value of future earnings, potentially leading to lower stock prices. A loss in central bank confidence can weaken the currency too, as foreign investors question the stability of monetary policy and the real returns of their investments.

Summary

Central bank independence appears across a broad spectrum and may be malleable in times of crisis. In normal times, we generally benefit from its autonomy, but when policy decisions conflict with political goals or public expectations, frustrations arise. Research highlights the importance of central bank independence, so a perception or actual decline in independence can unsettle bond and stock markets as investors anticipate a less disciplined monetary authority. Political pressure on the Fed is nothing new—today’s critiques echo past clashes, including a physical altercation in 1965.

In the U.S., the Fed is created by Congress, governed by presidentially appointed board members, and guided by congressionally defined mandates. This structure creates accountability and transparency, while also providing enough autonomy to navigate the economy effectively. At Blue Trust, we continue to monitor these dynamics closely, recognizing that while President Trump often tests boundaries, he is also mindful of market reaction to policies and pronouncements. Ultimately, we believe the Fed will maintain a level of independence consistent with the range exercised throughout its more than 100-year history.

For more insights and real-time reflections, follow Brian McClard, Chief Investment Officer, on X (formerly Twitter).